Hank May: Morgana

How do we talk about suicide?

Directed by Jo Garrity

Today's curated work holds a significant message, prompting us to present it in a slightly altered format. Our intention is to allow ample space for the story to be conveyed effectively. As observers, we frequently overlook the impactful experiences—whether positive or negative—that contribute to the creation of artistic endeavours. In an admirable effort to challenge the stigma associated with suicide, director Jo Garrity shares with us a deeply personal narrative behind the music video he directed for musician Hank May.

Morgana explores a sensitive and complex subject related to mental health support and suicide prevention. Can you share more about your creative approach in bringing humour, vulnerability, empowerment, and hope to this subject matter, aligning with Hank May's music?

I was in Spain on another one-way ticket when Hank May released the first single off his new album, I’m Just a Lover Now, the perfect anthem for a summer away from a film industry broken by labor strikes, revealing that even for best-case success scenarios, returns seemed more diminishing than ever. Hank’s defiant, jubilant manifesto—suddenly amped by a pop production departing from his indie rock roots—hit dead center. It was Born in the USA for the burned out, debt-ridden children of Reaganism. I played it on repeat, played it roaming the ancient streets of Barcelona, played it into the headphones of the woman I had found myself walking backwards into a blissful, undefined relationship, careening towards something heavy:

I’m just a lover now, don’t give a fuck about what’s in the bank or what’s my name

Shut the fucking city down, that way you can see the sky turn blue

And I’m just a lover now, don’t give a fuck about success in the last ditch left

I’m just a lover now, that’s how it’s turning out — final form — who I grew up to be

What a radically simple idea. To be just a lover—of a life, of another, of who one is. To be fully enough, unconditionally, without waiting for some validation on layaway. Hank’s song captured something in the air, when it felt like careerism was going belly-up and the American dream, if it was ever anything but a veiled nightmare, was precipitously on the verge of awakening. It was in the same spirit I had fled Los Angeles. A string of abruptly closed doors—a relationship, a training program, work prospects—had coincided with a deepening depressive episode culminating in the early spring with the return of my first suicidal ideation in four years. I had dealt with depression and suicidal episodes periodically since I was 19, however this time was different: I spoke up about it, immediately. To my partner, to my therapist, to my family. By now I knew the signs and the thresholds, and the fact that I couldn’t call this anything else. I was advocating for myself, researching more support options should I need them, including the possibility of returning to medication, partial or in-patient hospitalisation, and also, a promising new psychedelic therapy for treatment-resistant depression. But it was prohibitively expensive. Then, as a birthday present, my partner gifted me the funds to try ketamine infusion therapy.

Over two weeks in May, I underwent six, hour-long infusions, tripping hard in a medical office in Century City, swaddled under blankets, reclined in an examination chair, beneath an eye mask, listening to instrumental music. Among the many things the infusions were showing me — in a realm where linear time and language hardly stuck—I was learning about the impeccability of timing. It’s all unfolding. All of it, in its own way, in its own time. A grand, mysterious process. One that made itself evident the night before the final infusion, when over the phone my partner left the relationship. The therapy was a parting gift. I felt oddly prepared to meet the moment, like a rising pressure suddenly released, after two months of deteriorating communication over long distance. With this last door closed, I asked myself what I wanted then, where I wanted to be, what an ideal scenario looked like. I thought of the place I had reset before the pandemic, where I had reconnected with adventure and joy, had found a way to dance in life again. Within two weeks, leaving a key under the mat, I was in Spain again.

That summer, renting a room and writing from a cafe, I worked on an essay collection on mental health and psychedelic therapy, synthesising my recent experiences with a longer view of my mental health journey, sharing more openly than ever before where I had been. I was growing ready to share what my experiences with suicide had taught me. To honour them, to heal, to free myself from shame, and to advocate for living. To help. But how do we talk about suicide? It’s a fraught subject. Loaded with stigma, trauma, a persistent feeling of intractability on all sides. Where does one begin without freaking people out, retraumatising some, or worse — as studies have shown, when suicide is covered irresponsibly — even spreading more harm. It’s been marketed as a damnable sin, a committable crime, a supremely selfish act. What if we could reframe? In recent years I had departed from the thinking that suicide was about wanting to die, but instead fighting to live. It was when you were no longer shielded by the things that kept you safe, that the fight became perilous. And though I learned never to claim final victory over depression, with age I have strengthened my resources, I have grown. I advocate for myself better than ever before.

In the effortless spontaneity of our summer together in Barcelona, I talked to her about how I had wanted to work with Hank after first seeing him at a free show at Zebulon in LA the year before, where his five minute ballad about the misery of online dating, High on LCD, again gut-punched me. His music was choked with pain and comedy, sorrow and sweetness. After that first show I walked up to him and awkwardly introduced myself, mentioning music videos, but he had already released his first album. The timing wasn’t right, as I was learning was always the case with these things. With everything. At the end of August, she and I said goodbye, for now, when I left for California with a plan to work a five-month freelance job, pay down debt and build some savings, and return by early spring. If I wasn’t able to admit it was for her, for whatever this transcendent relationship was becoming, I knew it was to give living in Spain a real shot. Sparing sentiment, we parted with a quick kiss and a besito ciao, a joking good riddance. Watching from the taxi as she marched steadily back to her apartment, never looking back, I caught the lump in my throat. All summer we had taken leaps together—our first date, starting with a nervous drink before a terrible movie, unfolded over fifty-one hours, and no one was kidnapped. This time, leaving Barcelona, leaving it to chance, the leap swelled in my stomach.

Working on a music video involves a close collaboration with the artist. How did you work with Hank May to translate the themes of the song into a visual narrative? Were there specific aspects of the music or lyrics that inspired key visual elements in the video?

The first time I heard Morgana was at a small club in Hollywood where Hank was rehearsing the new material at a weekly residency in the month before his second album release. From a stool at the back of the bar, I revelled in his songwriting, shaggy and wild, savouring the taste of live music for the first time since Spain. I had crash landed back in LA, the freelance job evaporating as I stood in U.S. customs, and spent days deep-cleaning an apartment returned ragged by nightmare subletters. With no money left, I had scrambled into an onerous temp office job, making a harrowing hour-long bike commute next to pissed-off LA traffic. Staring at Spain on a world map hung in the break room, the road back looked long. Somehow, she and I had found ourselves falling into a daily pattern of communication— songs, messages, the occasional overt love poem in so many words—and it seemed the distance and uncertainty, rather than dissipating the connection, gradually, sweetly built it further. After I’m Just A Lover Now, she had encouraged me to pursue a video for the upcoming album, rooting for it from afar. In that small club, mid-way through the set, a song suddenly made me sit upright, its chorus resounding:

There’s a will, there’s a way, there’s a what the hell

This is not a universe in which I kill myself

He sang the chorus five times in the final minute of the song, in case you missed his point. My hair rose, heart pounded, a sensation of either starting to laugh or cry. I was unnerved by the boldness of his claim. Could he say that? For anyone who had experience with suicidal depression, the idea seemed revolutionary. My thinking went, if I had been surprised before, with multiple episodes since I was nineteen, how could you guarantee it would never happen? I was awestruck at Hank’s radical declaration of self-advocacy, of resilience and joy, what an antidote it was to worn out narratives of helplessness and victimhood — his mantra was a shield that needed to be shared. I knew immediately, this was the song for a video treatment. After the set I walked up to Hank at the merch table, oddly at the very moment the house music cued up another song I knew well, Alvvays’ In Undertow. I pointed up at the speaker, told him I’d directed that music video too, that I thought he was amazing and hilarious, and we should consider doing a narrative music video together. This time, the timing was good.

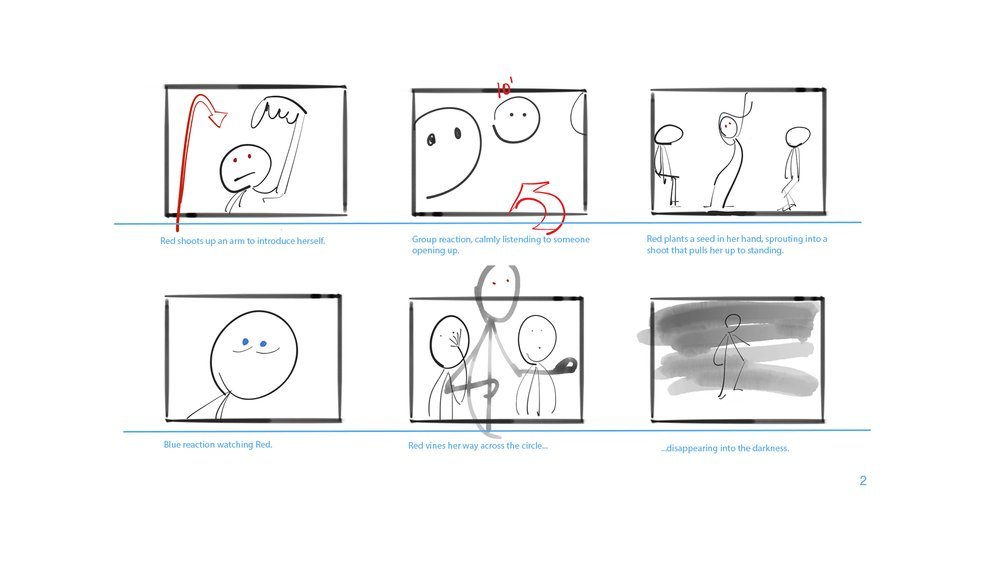

I went home that night with a burned CD of the unreleased album, along with a cutting from the plant that appears on its cover, a springy succulent nestled in a blue ceramic skull. Hank had given me watering and lighting instructions, but mostly told me not to fuss with it too much. Plants grow in their own way, in their own time. Listening to the album through track seven, Morgana, confirmed itself as the most exciting challenge. I listened to it over and over, its funky, pulsating groove seeping in deeper and deeper, revealing more each time in the sonic nooks and crannies of its intricate production. I began dancing. I danced as I danced in Spain, shedding self-consciousness. Practicing falling. Something was coming through, a crude language of movement. The thumping groove had me twitching and sliding, straining and releasing, and with the opening lyric — I’m the fruit picker, dripping red — I sensed a personal introduction, an entrance being made. My hand shot upward, pointing back down at me, as if getting something off my chest, coming clean. “Yeah, I’m the fruit picker, that’s me.”

I recorded two takes of an interpretive dance to the song. I couldn’t put it into words yet, but a concept was taking shape even in that early sketch, something about overcoming that thorniest of ideas: stigma. The invasive weed of mental health, antithetical to healing and growth, sapping resources from more delicate processes. There was a story emerging here about breaking through its isolating force in order to reach out, vulnerably and powerfully, to show all of who you were, to connect. The introduction that was being made here, by a character I found myself simply calling Red, said, this is who I am, this is where I’ve come from, and this is what I’m here to share. It’s why I’m here. Like me, they were coming out of the closet about their experience with suicide. They were unburdening themselves of stigma. They were trading in old narratives that taught them shame for something new. Something powerful. As powerful as the shield of Hank’s mantra. They were finding growth, once a seed in a dense place of insularity, now sprouting into a new stage of evolution, into a new light.

There’s a will, there’s a way, there’s a what the hell…

I sent the dance video to Hank, fully prepared for silence, maybe a quick no-thanks. The freelance filmmaking path had taught me well the habit of simply stacking rejections. Then: “Hey Jo, you are such an amazing dancer!!! I love your video, it made me love my song again, I had a moment with that song on the chopping block but I’m glad I kept it, and watching u dance to it is like coming full circle back around to digging the song again.”A track saved from the chopping block, a chance reconnection during an unscheduled stop back in LA, and now our mutual digging of the song—it all felt like kismet. On a video call, with Hank sitting at the wheel of a parked car, I felt bashfully like I already knew this guy, like someone I had grown up with, or maybe a version of myself. In his eyes I could sense we’d both lived through things, near-total losses. I had read about some of the experiences that were the glycerine fuel for his first album, a blazing plume of grief, pitch-black comedy, longing, a scream of survival. Sitting there in the driver’s seat, Hank was careful not to explain too much about Morgana—going off the dance video, he wanted me to follow my own instincts. Even so, I asked gingerly about the plant imagery in the lyrics, on the album cover, and sitting in my kitchen. He talked about falling in love with a succulent that hung above his bed, how caring for it had become therapeutic for him. But he also had learned not to helicopter-parent it, not to control it too much. To let it grow in its own way, its own time. Someone had told him that succulents thrived on neglect. The translation back to mental health metaphors wasn’t exactly one-for-one—thriving on neglect sounded off—but I understood the meaning. There were less than helpful ways we could care for ourselves, especially when that care became about attacking symptoms, cultivating mistrust, further internalising stigma. We talked about the tonal line we would be walking with this video, to do right by a sensitive subject we both had experience with, but also avoid the pitfalls of being too corny, or self-serious. We were taking a leap, honoring and having fun too.

But for you, baby blue, I let go

As you grow watch you slo-mo explode

We both acknowledged the project would have to be done as the most passionate of passion projects, scrappier than even most music videos came, with the only possible funds from the record label—if there were going to be any at all—being nominal at best, hopefully enough to cover lunch for the crew. The parameters I was setting for myself was a one day shoot with in-kind equipment and a volunteer crew. We confided that neither of us could afford to go out of pocket. I was already scraping to hold onto my apartment for another month, and time was ticking. Depending how late the production date landed, I might be timing it to the last ride out of town, either to my brother’s house, or maybe—just maybe—to Spain. I was inspired to make this one count. After years of chasing the next music video project, I finally had an artist on the line, a song I could bring myself fully to, and a wide berth for creative freedom. Also, no resources or collaborators, yet. There was work to do.

“I had dealt with depression and suicidal episodes periodically since I was 19, however this time was different: I spoke up about it, immediately”

Can you delve into the aesthetic choices made to create the visual environment, and how did the use of motion-control camera systems contribute to the overall visual impact?

I put together a video treatment, an experience that after enough rejected pitches I was growing to understand as the balance between details and dreaming. Like a screenplay, it was a provisional document, one that was bound to adapt to the realities of a production, and the contributions of a team. I researched references, pulling stills from films and music videos, scribbling visual and narrative ideas, tracing the arc of a story. I sat down with my friends Miranda and Wes, who I tapped to produce and direct photography, to talk through the concept — a hybrid narrative/dance video using improvisers to play members of a therapy group that goes off the rails, in an uplifting way. Both Miranda and Wes were game, diving in to assembling the troops, calling in favours using the pitch — imparted from me — that this project, though having no money, did have the potential to do something new, possibly even do some good. Wes connected us with Hyper RPG Studios, where he had been trained on an impressive motion-control camera system and a virtual production environment, technology used on similarly modest productions like “The Mandalorian,” except instead of Disney this one was packed into a two-car garage in Studio City. Malika and Zac, the consummate independents who co-founded Hyper RPG, opened their doors to us, eager to demonstrate the capabilities of the ingenious system they had built.

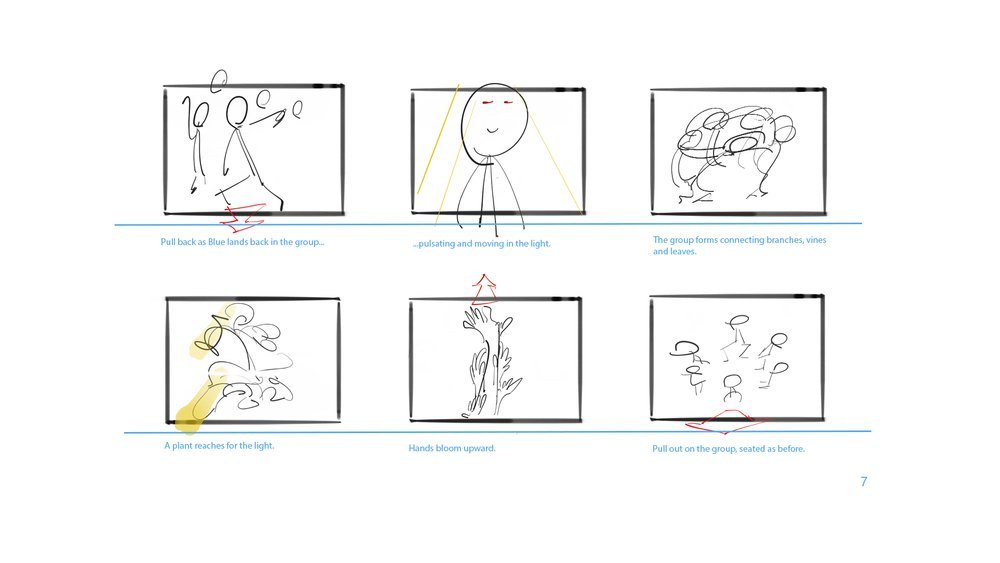

In the weeks before the shoot date, we took advantage of empty studio time to work with other-Jo, our wizard technical director, testing the motion-control robot’s capabilities, its programmable, superhuman arm straight out of a car manufacturing plant. It had no name, but it gave HAL vibes. We tested how tied to a performer’s movements it could be, what the trade-offs were in time and complexity for certain moves over others, and which shots we would prioritise, condense, cut. The storyboard and shotlist grew and contracted, cutting a narrative path Red would take to bring change to the group. Her reframing of the space, by raising her hand, breaking out of the circle, crossing into darkness, spinning Blue’s world around—along with her dance partner, the camera—would bring the audience’s reframing. Red’s act of expression, initially uncomfortable, uncertain, and vulnerable, would initiate a powerful growth process.

Also in play with the robot was an LED wall capable of displaying a virtual environment. Building a digital set to real-world scale, with volumetric lighting that could match practical lights in the studio, the environment displayed on the LED wall adjusted in real-time to the changing perspective of the camera. Initially, for simplicity, I had started with a circle of chairs in a bare space. Now with the studio’s tech in play, I still wanted to give us the flexibility to shoot both ways — one side of the set using the virtual environment on the LED wall, and the other side, against darkness. This bisected set design offered a few advantages: first, with a directional light source, like high-angle, sloping sunlight from windows, the audience would always be oriented in the space no matter where the camera pointed; and second, having the flexibility to shoot beyond the confines of the LED wall would allow for high-framerate, slow-motion shots, wider framings, and the possibility of handheld camerawork, to grab coverage if we were running low on time. And we already knew it was going to be a sprint.

With Malika’s expertise in virtual set design, we expanded on the plant motifs and took inspiration from greenhouses, those light-filled spaces where careful work was being done. I remembered a place I had visited on a weekend visit to Madrid, the Palacio de Cristal, an intriguing and serene glass enclosure full of light yet barren inside. Its feigned separation, its transparency, seemed to pose a visual question of what was being kept in, or out. With our set design, I wanted to unify this wall of light with the darker recesses of the space, to avoid a simple binary. The dark wasn’t an adversary. It was a teacher, teaching the value in the full spectrum of emotions, even the uncomfortable ones. It was necessary, the place Red went when leaving the circle, to gestate, and later, to germinate. The dark held a place of honour, without need for fear or repression. And it was never totally dark — even in the farthest recesses, beings were able to reach out, bending toward the light.

The concept involves a mental health support group finding catharsis through kinetic release. How did you approach choreographing the movements to convey the emotional journey of the characters? Were there specific dance or movement styles that resonated with the themes of the music and the video?

Tone was perhaps the most important element to land, the tightrope walk we knew we’d be walking with a song touching on suicide. As keeper of the story, it was my job to keep guardrails on. In years of improv training, I came to understand humor was often as rigorous and delicate as any dramatic form—one false note and the sensibility could be thrown. Considerations arose: what kind of comedy were we playing in? What was given as ordinary, and what stood out of it? Where were we being given permission, safety, to laugh? And what was the right balance of authentic, grounded emotion? One of the references I had included in the treatment was the Daniels-directed, full-throttle music video for DJ Snake and Lil Jon’s Turn Down for What. More than just a deliriously fun ride, the magic trick of the video for me was its ability to convey a feeling of safety to the audience, in spite of the outrageous, boundary-crossing behavior we were seeing. Behavior that, on paper, could be read as aggressive or alienating, instead was held in a delicate balance of play and honest reaction. Watching them, we remained with these characters, not separating ourselves to judge them, or pit them against one another. With Morgana, it was the same spell we would be attempting to cast. The direction I gave to the ensemble, improvisers I knew had a committed deadpan in the face of absurdity, was that they would be responding to Red’s contributions as if she were sharing in words instead of movement. Opening up to the group, getting vulnerable, and sure, provoking some polite discomfort from some. But that’s what we were doing here, inviting people out to come out of their comfort zones, making it safe, reframing. Ultimately, we were all coming along for the ride.

I wanted to work with a movement director who could help refine and translate the initial movement ideas into a kinetic language for the ensemble. Collaborating with Sebastian, a theatre director and choreographer, who with his company Four Larks was well-versed in staging bold, experimental, hybrid work, we refined the visual ideas both for Red and the group’s movements. We expanded on the plant motifs in physical, human form: climbing vines, shaking leaves, supporting branches, cycles of tension and release, juxtapositions of smooth and sudden motion, like those seen in timelapse videos of plants growth. Wes introduced me to Stephanie, an inventive and versatile dancer, who I sat down with at a cafe to talk through the concept. I walked her through the rough sequencing, arriving at the break into the final five choruses, where I had imagined Red sending Blue into a spin by kicking the leg off his chair. But as we both chewed on the idea, we agreed it didn’t feel right — it was forceful, imposing, too close to the “snap-out-of-it” mentality, the stigma we were trying to reframe. Stephanie suggested something more subtle, profound: a whisper into Blue’s ear. We had found ourselves sharing about our mental health journeys, about the gestational timescales of insights and healing. Walking deeper into these ideas, attempting to find expression, we had reached a surprising vista, tears in our eyes. We wrapped the meeting, hugging, as Stephanie left to flesh out and rehearse Red’s choreography.

We managed to bring Hank into the studio a day before the main shoot, grabbing solo shots and lightening our load for the next day. It was the first time I’d seen him in person since the show. Now he was here, taking a total chance on us, being asked to sing in double-time down the barrel of a hulking, high-speed robot that stopped for no one. We were all a little nervous, and I knew that as much as we had mapped and tested and tweaked, planning would take us only so far. Taking a breather to shatter an antique chair in the parking lot with Miranda, we tossed the pieces around Hank’s feet as he lept down onto the stage. Filmed at 500 frames per second, it was slow enough to turn a few seconds of action into minutes of playback. We checked our work on the monitor, scrubbing through the footage — nothing, nothing, still nothing — then, the moment zipped by. Reverse. Play. At 24 frames per second, the chaos was serenely beautiful, a delicate unfolding we couldn’t appreciate on our timescale, here tossing wood scraps in a converted garage in LA, smiling at it all.

It’s all unfolding.

“The parameters I was setting for myself was a one day shoot with in-kind equipment and a volunteer crew”

Were there insights you learned about mental health support in the process of making Morgana? Can you share any specific challenges you encountered during the production and how you overcame them?

Our mental health is inextricably tied to our environment, our communities, our national discourse and priorities. The American Dream taught us it was everyone for themselves, in success and in failure. Advocating for interdependence doesn’t fit this agenda, doesn’t move the merchandise. The goal of the project, to speak from experience and empowerment about mental health and suicide prevention, to reframe on the topic, was about that advocacy for interdependence, about rejoining the collective. I was no longer going to believe in a narrative that told me this was about my personal failing, my weakness, my frailty, my liability to some agenda. Instead a new narrative had taken its place: this was about my resilience to fight for what I loved — living — about the growing ability to discern the value of that love, and, significantly, to share it. Openly, out of the shadows, directly in the eye of stigma.

On the morning of the main shoot day, driving a borrowed car with a bad tire, with an overdrafted bank account, I recorded a message to myself: “Just a reminder. You were given $500 to make a music video. You’re on your way to pull off a small miracle.” Setting up the camera, with the cast arriving in their wardrobe, the clock began its advance toward a hard-out of 6:00 PM. Racing through the shotlist, the team suddenly became an organism. Miranda, marking slate, Sebastian, responding to Stephanie and the ensemble’s movements and pitching adjustments and. Wes and other-Jo, operating camera and robot with our time spent practicing together coming to the fore. Hustling through a few takes of a shot, jettisoning on others — “Beautiful, moving on!” — the company would spontaneously break into cheers. We were doing it.

In the final minutes we reached the shot of Red’s sprouting from a seed. Darren lay in the dark behind her curled form, on cue raising an arm above Stephanie’s back, unfurling his fingers. Then she rose, her arms emerging first, pulling her upward. The air caught in my lungs. I looked around, realising then what we were all doing here. All that had bloomed to make this moment. “That’s a wrap,” I creaked, at the scheduled minute. Before rushing to load out, I circled us all onto the stage, kneeling down in the glare of the artificial sunlight, uncertain what I would even get out. Our band of believers, from nothing, had made magic. All of me stood at the edge of my skin, about to burst into tears, managing: “May it bring movement, creativity, joy. And healing.”

And now?

I am in Spain on another one-way ticket, again. In part, to tell her how I feel. To let go of expectation, to dispense with regret. And in larger part, to create the life I have dreamed of, that is still being dreamed.

We don’t know how the story ends. Accepting this—it’s the beauty of living.

Director: Jo Garrity

Producer: Miranda Peters-Lazaro

Key Cast: Stephanie Kim

Key Cast: Hank May

Key Cast: Darren Hale

Key Cast: Bonnie He

Key Cast: Jennifer Polania

Director of Photography: Wesley Rodriguez

Executive Producer: Malika Lim Eubank

Executive Producer: Zac Lim Eubank

Editor: Doug Yablun